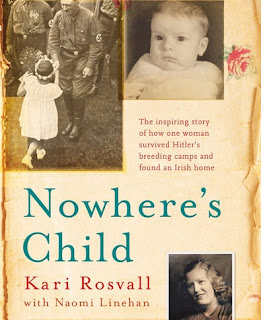

Nowhere’s Child by Kari Rosvall: An unfettered struggle?

Nowhere’s Child by Kari Rosvall is about a woman’s valiant struggle to ascertain and accept her birth identity. Inter alia, the Lebensborn policy of the Nazis involved turning Norwegian women into breeders, with children fathered by SS and German soldiers. Kari, born in 1944, was one such baby.

You can imagine the credits fading out and a title: Norway 1944, as a bunch of evil black-uniformed Nazis ship containers of babies off towards the Fatherland, by train or by truck or by ship. The beginnings of a Marvel movie, it seems, the first of a franchise, featuring the origins of a superhero? No! This actually happened.

But her easy-going attitude – in spite of her claims to be a bit of a worry-wart, and while dogged by setback and occasional rough patch – is very Irish.

But this is the third paragraph that I've started with but.

She is perhaps less restricted in chasing her story than she would have been in the Ireland of John Charles McQuaid. Not to detract from her efforts, or the uncertainty about her background, but we can be thankful that the story can be told at all. We can be grateful for a more progressive Scandinavia while contemporaneous Ireland dozed through the Swinging Sixties. We can be grateful too, to Kari Rosvall herself, in her courage over sharing her background, and her powerful story.

Start on the first page and you certainly won't stop there. It's really strong and impressive writing.

The Nazis also snatched blond-haired, blue eyed children off streets in Eastern Europe for adoption by German families.

You can imagine the credits fading out and a title: Norway 1944, as a bunch of evil black-uniformed Nazis ship containers of babies off towards the Fatherland, by train or by truck or by ship. The beginnings of a Marvel movie, it seems, the first of a franchise, featuring the origins of a superhero? No! This actually happened.

Kari claims in the buke that the Lebensborn kids were regarded as unsalvageable human beings, the postwar Norwegian leaders of the time viewing any effort to raise them in Norwegian society as being akin to house-training cellar rats as pets. This is the sort of prejudice she would have had to face.

From an Irish perspective, however, Kari’s life over the last sixty years and more seems implausible for other reasons.

What is striking while reading – alongside her hugely interesting family saga – is the incredibly progressive Scandinavian society in which she lived, until her move to Ireland some years ago:

1. Her first marriage fails after having their child.

2. She moves careers more than once in an era where people attempted to hold a job for life.

3. As impossible as it is for Kari until she reaches retirement age, finding any information on her background under Irish law would have been difficult, from what we hear of the struggles of adopted children in Ireland in the media.

There is little talk of financial difficulty, which may have been present while raising a child as a lone parent.

But Kari's focus on story, rather than on the everyday struggles, is a testament to the strength of her narration and the power of her will. Doubtless she had these or similar issues just getting through things.

But Kari's focus on story, rather than on the everyday struggles, is a testament to the strength of her narration and the power of her will. Doubtless she had these or similar issues just getting through things.

But her easy-going attitude – in spite of her claims to be a bit of a worry-wart, and while dogged by setback and occasional rough patch – is very Irish.

But this is the third paragraph that I've started with but.

She is perhaps less restricted in chasing her story than she would have been in the Ireland of John Charles McQuaid. Not to detract from her efforts, or the uncertainty about her background, but we can be thankful that the story can be told at all. We can be grateful for a more progressive Scandinavia while contemporaneous Ireland dozed through the Swinging Sixties. We can be grateful too, to Kari Rosvall herself, in her courage over sharing her background, and her powerful story.

We can draw lessons from it.

The book shows an under-reported aspect of National Socialism made manifest in the early 1940s. Kari's life-affirming achievements are a remarkable rejection of the very philosophy that brought her into existence.

Start on the first page and you certainly won't stop there. It's really strong and impressive writing.

You can follow Kari's co-writer, Naomi Linehan, on the Twitter.

Buy the book on Amazon or in any good bookshop.

Comments

Post a Comment